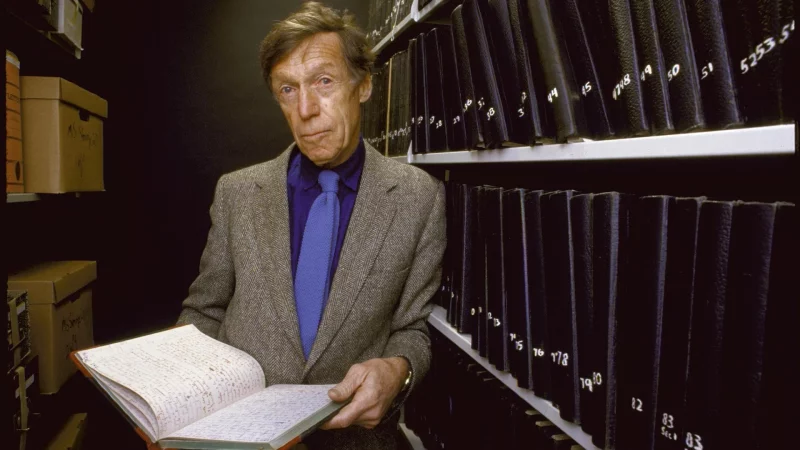

Zachęcamy do obejrzenia nagrania, w którym nasi amerykańscy absolwenci – Alex, Kaelyn i Sarah, dzielą się swoimi doświadczeniami z rocznego pobytu w Polsce jako asystenci nauczania języka angielskiego w ramach programu Fulbright English Teaching Assistant.

Fulbright English Teaching Assistant Program to stypendia trwające 9 miesięcy dla amerykańskich studentów:ek i absolwentów:ek. W trakcie pobytu w Polsce prowadzą zajęcia z języka angielskiego na polskich uczelniach wyższych. Komisja Fulbrighta umieszcza stypendystów w instytucjach, które wyraziły chęć przyjęcia kandydatów:ek i zostały wyłonione w drodze otwartego konkursu.

Czy pobyt w Polsce sprostał ich oczekiwaniom? Co ich pozytywnie zaskoczyło, a co stanowiło wyzwanie? W inspirującej rozmowie poprowadzonej przez Aleksandrę Braumańską, koordynatorkę programu ETA, Alex, Kaelyn i Sarah opowiadają o swoich obowiązkach w ramach grantu, zaangażowaniu w życie lokalnej społeczności, poznawaniu polskiej kultury oraz dzieleniu się kulturą amerykańską – a także innych aspektach bycia Amerykaninem na rocznym programie wymiany w Polsce.

Alex, absolwent University of North Carolina-Greensboro, pełnił rolę Fulbright ETA na Uniwersytecie Szczecińskim, Kaelyn (absolwentka Florida Gulf Coast University) na Politechnice Bydgoskiej, a Sarah (absolwentka University of Nebraska-Lincoln) na Uniwersytecie Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej w Lublinie.

-If you were to name two benefits of your grant, what would it be?

-The people and the people.

-Alright, hello, welcome. Thank you for joining me today. I’m very happy we’ll have a chance to talk a little bit about the English Teaching Assistant Programme, which is one of the programmes at Fulbright Poland that is addressed to U.S. citizens. Before we dig into details, I would like to say ‘Congratulations’ on completing your Fulbright Year as an ETA in Poland. You have literally just graduated because we have it over here right after the graduation ceremony, and how does it make you feel?

– I can’t believe it happened, I can’t believe it’s over.

-It makes me feel sad, because these are all lovely people, but it’s you know, it’s a wonderful thing, right, it is good. It changed my life.

– I’m definitely feeling sad leaving Poland and my city, so I can’t believe how fast that [nie mogę zrozumieć]

– Surreal, it really is.

– So, let’s go back to the beginnings for a minute – the time when you applied. What made you apply for the Fulbright programme? Was there anything particularly interesting in the programme description, and how did you find out about it? Was it recent, had you thought about it before?

– I can start perhaps. So I actually first heard about the Fulbright programme in general when I was in my first year at university. Someone came to talk to our class about fellowship opportunities, and so they had like, uhm, they talked about being a Rhode Scholar, a Fulbright Scholar, other things, all kinds of things. And so our university had a person who was in charge of you know, advertising it and helping students apply to those things, and I was, you know; this was five years ago now, and I was not in a place to apply right, I had to finish my degree, but it was in the back of my mind the whole time. And then I started looking into it and yeah, the reason I chose Fulbright Poland specifically was because of the programme, the nature of the programme. Actually I have no family ties to Poland, I am not Polish, people often think that I am but I am not. But the programme description itself was the big thing. So it was teaching university students which I liked, and the description also had a STEM focus in English, and so that was ultimately why I applied. And it worked out that I didn’t teach anything with STEM, but like I don’t think I’m missing anything at all, like I’m happy with me, right. But that’s my story. That’s how I found Poland in the first place, found Fulbright in the first place.

-What about you, Kaitlyn?

– So for me, I first heard about the word ‘Fulbright’ ever in my life my junior year of college. The fellowship office I was working with told me about it and I went online at home and I looked up details and I’m like ‘This has nothing to do with what I want to do in my life, I want to become a doctor so how does this apply to me?’ And then I was talking to an advisor about this and he helped me understand that some of these skills I would be gaining from Fulbright transfer to becoming a better doctor towards the communities I would be working with. So he really encouraged me to apply and I’m really glad I did. Why did I pick Poland? So my background is in cancer research and I learnt about Maria Skłodowska and her work with polonium and radium and how it led to cancer treatment in terms of radiation. And something I’m very passionate about, cancer education, really encouraged me to apply. And as a Black woman I’m like uhm this is a very homogenous community, do they know more about me, can I share more about myself. So, that’s the reason I applied.

– Okay, Alex, what’s your story?

– I first heard about Fulbright during my time as an undergrad. During this time, towards the end of my studies I knew that I somehow wanted to go back overseas and I always wanted to come back to Poland. I had visited the country a couple years ago for about two weeks and I really enjoyed being in Warsaw. In the last couple of years I was able to learn more about my family’s history in Poland. So my great-grandfather came from the southeast of Poland, immigrated to the United States in the late 1920s. And over the past couple of years, my grandpa and I had many conversations about my great-grandpa and where he came from in Poland. And we always kind of dreamt about us coming to Poland together. And we always kind of, I thought about travelling and kind of retracing our family steps in the area. So it had a lot to do with my family’s connection to Poland. I’ve also been very interested in this country ever since I was in elementary school. Poland this kind of part of the world; we don’t really talk about it too much in the American public school system. I knew I had an opportunity like Fulbright where I’m able to live in a country for right under a year and this would allow me to not only kind of discover my family’s heritage but also allow me to learn more about the community that I have family ties to and then be able to kind of take everything I know and almost represent my own Polish community here when I’m back, when I get home.

– So you talked about your educational background – what teaching experience did you have before becoming an ETA?

– So as an undergrad I served as a teaching assistant for some STEM majors like biology and physics. And I also was a tutor at our academic center where I was tutoring science, math and physics. And through this cancer research club that I was working with I spread a lot of cancer education through our university and our community.

– So, Molly, what’s your educational background and what teaching experience did you have coming here?

– I taught chemistry lab for university students and I also taught a discussion-based class in the university honors programme at my institution. And I also did an after-school club in the public school system in my city; it was called ‘Science, sustainability and saving the world’, so these kids were very excited about it. So that’s what I did, very STEM-based, but maybe Alex, yours was a little different.

– So I wasn’t saving the world with middle-schoolers, yeah. My experience with education I think begins early on in my undergrad degree. There was a YMCA in my city where I started working with their after-school programs, a lot of work with elementary-schoolers and middle-schoolers and then when I decided that I wanted to become a teacher I had some student teaching experience with the middle grades and then with a third-grade class, and then also in college I volunteered in a highschool classroom. So really a lot of I think informal experience through the YMCA and then I did have an opportunity to student teach with elementary and middle school students prior to coming to Poland.

– So if you could describe the tasks that an ETA has – what was included, what was your schedule like, what was expected from you?

– Well I think, personally; these two can agree or disagree, but I think it really depends where you are. So I had two very different experiences depending on my semester actually. The first semester at my institution I was teaching a lot of classes, I was teaching four different courses a week and that was a lot of preparation. I had to grade essays, I was teaching writing; it was very overwhelming to me at first and I got used to it but the workload itself was pretty heavy. The days looked like waking up, going and teaching, for me anywhere from two to four classes, and I would often have my office hour and I also had a Polish language class that I went to in my first semester. But that was not sort of a task or a duty. But the second semester was a little bit more fun, I got to teach American culture and I had co-teachers so the workload was shared so I did not have to grade that many essays. It was a lot of discussions and I joked to my students that that was my Polish culture class because I also learnt a lot. But yeah, it was very different depending on the year but I think that’s the nature of this type of experience. I mean you’re the native speaker and I think in my institution they wanted me to kind of be able to work with as many students as possible, but you know, it might depend.

– So were the classes that you taught big, how many people more or less did you have?

– It depended on the class; I had anywhere from 6 people which was very small to 16, 16 or 18 maybe. So the class was small enough that we could have good discussions. It was good, good sizes.

– What about your classes, how many classes did you teach and how many students or faculty members?

– So for me each semester it was about five classes. And I was teaching second year general English, I was teaching third-year technical English for IT students and I was also teaching a group of PhD students. Last semester I did like Tuesday and Friday and then this semester I was Monday Tuesday. And in addition to that this semester I was also teaching finance students, Master’s degree students so that was really fun, and I did not work with faculty, my classes were anywhere from 4 students to 15-ish. So my favorite group to teach were my second-year IT; they loved talking to me and I just loved them. They give me real hope for the next generation.

– That sounds very hopeful, yes. Alex?

– Yeah, I taught five classes throughout the whole academic year. I had four conversation classes and one academic writing class. All four of my conversation classes were my first-year university students and then the academic writing class was a group of first-year and Master’s students. I think that throughout the past nine months of teaching my conversation classes; I remember when I found out the courses I was teaching I wasn’t sure what was required of a conversation class, but I quickly learnt that you know, your role as a teaching assistant in the room is more like you’re like a facilitator in giving your students that space to be comfortable and I like how Sarah mentioned earlier that it was her Polish culture class on learning from her students and I had a very similar experience to that.

– Was the workload manageable for you?

– It was definitely manageable. I’m really grateful for my university and that they gave me quite a bit of autonomy in what topics we discussed in class, in what projects I asked my students to do through the academic year and so a typical week I would have class two days a week and I would be able to lesson-plan and grade and again I was given a lot of autonomy so I could choose what we were talking about and I tried to, you know, be creative with my plans and give my students a chance to also be creative as we were doing the plans. So the workload was very manageable, I think my university gave me a lot of flexibility when it came to creating lesson plans and facilitating them.

– Kaitlyn, was that the case with you as well?

– It was very much the case. My school department, they pretty much supported me in anything that I did and they gave me full autonomy to teach how I wanted to teach. Something I noticed was that my students were very used to a lecture-based course and I turned that around into they’re moving, they’re speaking and it’s less me talking.

– Was that autonomy you were given a blessing or a burden?

– Both.

– I found it to be very much a blessing. Kaitlyn mentioned that students in our classes are very used to more lecture-heavy, the teacher is like the main character in the class, but with the autonomy that we were given and kind of knowing what we know about language development to kind of put the spotlight on the students and give that space to work, to play with language. And so because I had so much autonomy I used the freedom to kind of create lessons that would possess the students as the main characters, so I was very grateful for the freedom to teach and facilitate my class.

– As someone who had both classes where I had autonomy and some where I did not I definitely think that being able to do what you want is a blessing. And perhaps it’s because in more ‘boring’ classes, academic writing. So when I was teaching, the teachers were basically telling me: ‘You can do what you want, but they have this test at the end of the semester where they have to write these three essays or they choose one of these three types and they need to know how to do it.’ And so you know, you can choose what you’re doing but you know, you don’t have a whole lot of room especially with that when you’re teaching to a test. So that made it I think easier in some ways because you know exactly what you’re going to prepare but in other ways you can’t really go with the dynamics of the student group, you can’t hear what they want to do and those kinds of things. So it’s nice to have conversation or culture-type classes where you can do that. So that’s just our opinions, maybe someone would prefer to just do what they need but you know.

– So you think it depends on the individual preference?

– Yeah, probably. What do you think?

– I think it’s helpful if the university at least provides guidelines for you to say ‘Okay, what I’m doing aligns with the students’ best interests’. But I’m definitely in favor of giving the teacher the authority and autonomy to do what the teacher sees as best for the group of students.

– I think it’s just relevant to the students, the freedom that I have to choose to make it relevant to the students.

– Kailyn, did you grade the students, either the tests or the exams?

– Yes I did, so I graded my students throughout the year with assignments, most of them were writing assignments and portfolios. And in the end some of my students got papers to write and some students got exams. This semester in particular my finance students, they got quizzes throughout the semester and assignments, they have portfolios that they’re making, presentations. It sounds like a lot but it’s not, I promise.

– Was it your initiative or were you asked to do those?

– This was my initiative. There were some goals I wanted them to meet in terms of speaking English in the finance world so I took initiative on my own to make those quizzes, exams, presentations, get them practicing speaking, working in English.

– Did you give grades, Sarah and Alex?

– I did, I had to sort of decide if my students were passing or failing, their fate was in my hands. They all passed except for the few that simply never showed up. The ones who came and tried they all passed. I personally really dislike grading essays, because after a while like 60 essays on the same topic is a lot so you really have to split it up. But you know, you get through it, you do what you got to do. The actual grade giving was not difficult, it was just the amount of grades that I had to give.

– For my conversation classes I was told that the students will be taking a final speaking exam at the end of not the winter semester but the second semester in the summer and I tried to create a class that would kind of simulate the environment of their final exam. So we had a range of topics we were talking about and I just used the rubric that the university gave me that included like pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar, all of the basic language functions and I kind of just tried to use my best judgment to evaluate the students to that criteria but of course giving them more chances throughout the semester to showcase their wonderful language capabilities. And in academic writing because I didn’t have a set curriculum of what the university wanted me to do I tried giving them assignments that I hope they found as sort of a space to be creative and like one prompt to 12 students and then they all take it in their own direction. So when I got to grading I didn’t have to be like ‘Oh I’m reading this academic paper’, I’m able to read 12 different perspectives on the prompt and see how the students make it their own. So it was more interesting than being a burden for me.

– Did you experience any challenges in terms of methodology? Coming up with the topics or how to plan a class in terms of the steps, anything?

– I think for me it was topics towards the end of the first semester or like mid-second semester I was running out of ideas, and with having autonomy there are no guidelines, so I was coming up with these on the spot. So to get ideas I was always talking with my cohort about what they did and also I was asking the students ‘Is there something you need to improve in your English skills?’

– So one resource was your cohort, the other one is your students, any other resources that you used when faced with methodological challenges?

– We do have resources available I think when there’s teaching concerns or fears [Or mentors’] Yes, mentors at universities, yes. I had a lovely mentor. They help you a lot.

– It was the same with me. I found the cohort to be the most helpful resource because we are teaching different classes but it’s a great resource to kind of bounce off our ideas from one another and you know, I can take what Sarah was doing in her academic writing class and be like ‘Oh okay, Sarah’s doing this, this might be in need for my class’ or ‘Oh so Kaitlyn is doing an interesting conversation topic’ and I think the best resource was each other.

– How long did it take to prepare a class?

– Depends on the class. Sometimes literally like a minute to think up what we’re going to do that day like ‘Okay, we’re going to play this game’ in conversation class. But then sometimes when I thought American culture I would kind of have a presentation where there had to be a discussion, a video then I would find all the sources and it would take like literally hours; but I mean it probably didn’t have to take hours, but that’s because I had more time, I had co-teachers so I could take the time this semester to do that. Last semester no way, but it depends on the class.

– I think for me it was similar like, a night before ‘We can do this!’ and then sometimes when it’s a specific topic I’m talking about I’m like ‘I need to research a lot of these things’ and it would take me like maybe up to four hours, from one to four hours for each specific class that I;m doing, so.

– Yeah similar to me so I would say that for each course it would take about 1.5 to 2 hours to lesson plan just once you have an idea what you want to do and then the most time-consuming part is trying to find resources or texts that you can use in class to build your conversation or writing activities. So for me the most time-consuming part was trying to find resources that I thought would be most effective for class but it took like 1.5 to 2 hours.

– But not each class like for me, I had eight groups of American culture students and I would just do the same thing eight times. I know it seems kind of crazy, I don’t know if you guys repeated things but it wasn’t each individual one.

– Yeah I did mention that I had four conversation classes so I would lesson plan for the conversation class, execute that plan four times a week, and then academic writing class had another lesson I could go with and you’d stop preparing a class for that week and then restart the process for the following.

– Something that was tricky when we used the same plan for the eight classes was that one group responded differently to something that you didn’t plan on so you had to improvise a lot.

– It’s kind of nice though that it’s not the same eight times because that’s a lot.

– What would you say was the most rewarding experience for you as an ETA?

– I can go first. There are probably like five that come from the top of my head but I’d like to touch on three of them if that’s okay. So I mentioned that coming to Poland I was really interested in trying to find where my great-grandfather came from. So recently I was able to go to the village that he went to, to go to the cemetery and see where different family members once lived which to me was very special. The second meaningful experience is related to what I did at the university. I had a wonderful group of students through the entire academic year. And in the first semester, coming into this grant, I really wanted to produce a podcast with my conversation students and there is a part of the project like a required task for my students where we had to meet outside of class and I would simply hit ‘record’ and talk. And I think being able to publish that was exciting. It felt very rewarding, mainly because some students were very excited to have a platform to talk about a topic that they are excited about and also they are sharing a little bit about Poland or their window of Poland to the English-speaking audience. So it was my attempt to try and bring some of Poland to American English-speaking ears, so I was really happy about that. But the podcast is not very good like in quality, but [it’s on Spotify] it’s definitely a meaningful experience like I had to talk to students like each one of them individually and know where they come from, what they like, what their interests are, and as you guys know I really love this country so being able to have so many conversations with my students about their life in Poland was really special and then trying to throw that content out there to whoever is interested was awesome. And the last experience was actually my favorite part about the grant. There is a primary school just south of my city, Szczecin, and I visited this primary school in total like ten times during this academic year and each time I went I would visit the same group of students and so obviously I got to know them, they got to know me, and it was nice because I’m working with primarily university students and then I got to go to this village where for a long time they had never met really a foreign person so they had never met a native American English speaker. So I think that being able to be in their classroom and talk to them and laugh with them was so awesome. It was really cute, I went there at the end of last week and they had made little cards and little American flags and it was really very precious, so that was my favorite part of my grant.

– For me, two things come to mind. So last year I had my students write papers, and they had to answer a specific question and I was reading one of the student’s paper and this is a pretty quiet student and he had mentioned that, he said that he had almost not tried at his language exam to get into the higher-level course which is mine and he said ‘I’m glad I did because I am with this teacher and she is the best teacher I’ve ever had my entire life’ and I was like ‘Oh my goodness’ and then I was working with EducationUSA Poland throughout my grant and one of the school visits I did was in a village called ‘Skąpe’, I hope I pronounced it right. The teacher and her family were taking me on a train and at the end of the day she says ‘Kaitilyn thank you for coming, this was the best day in my career’. And it caught me so off-guard I almost started crying and her students were great, they didn’t have a lot of resources but they were so kind to me, we made tiktoks. But that was really great. It just shows how many of these smaller areas, how much they value Fulbright, and foreigners in general, and I really appreciated that.

– It’s so hard to choose remarkable moments or special times. I have very similar things; school visits – big, you know I’ve been with kindergarten kids or students, I don’t even know if you can call them students, but kindergarten children and then teenagers and it’s a very special thing because of lot of these people have not had a chance to speak with a native speaker and to see when their English teacher says ‘ Go practice your English’ ‘Oh okay, yes’, but when you get a chance to talk with a native speaker then it’s like ‘Oh’. And then just having those students that don’t even know you just give you hugs. The students that I knew even, like my university students, I had three of them, and they’re very close in age to me and we finish our last class and they are like ‘Can we give you hugs?’ and I was like ‘Yes, you can’. There are so many good things, it’s so hard to choose from. There is so many good things.

– And then things are coming, next week; I still have next week still, so I’ll have my last class with my students and I already know I’m going to cry. My students are like ‘We got to take pictures next week’ and I’m like ‘You’re right’

– Let’s go to the not-so cheerful moments but I’m sure you’ve overcome them. What were your biggest challenges, both in terms of teaching and daily life? And how did you manage to cope with them?

– Shall I go first? I think for me I had literally never been to Europe or abroad before doing this so I decided to pick up and leave the midwest and move alone far away across the world. So I knew that adjusting would be a big thing for me but I had learnt way less… that’s not the right word. I’ve learnt a lot more about being able to care way less about what people think. As you know, I don’t speak Polish, I’m learning but I’m not fluent. And so you go into these places and you don’t speak the language, you don’t know the culture and you’re going to embarrass yourself no matter what you do. You’re going to embarrass yourself no matter what, we’ve all had those moments, we shared them with each other to know that we’re all in this together. But I think that overcoming the adjustment period and sort of realizing that it’s okay to be the clueless foreigner sometimes, you just have to do it. But it’s really all of the things that come with adjusting. The language barrier was big for me; I think this was the biggest problem I had in terms of teaching. The workload was one thing but in terms of managing the classroom and working with the students I felt like I was prepared for that, it wasn’t the hard part; the hard part was existing as a human in this new place. So pretty general things but things nevertheless. Maybe it’s the same for all of us, but I think there may be some different experiences as well.

– Was the language barrier a problem for you as well?

– Yes. I felt like a lot of people in Bydgoszcz didn’t speak English and some didn’t really want to speak English. And I saw that in some of my students; they know English but they don’t want to talk to me. That was really hard so I relied on Google translate and my Polish friends, especially when I had to go to hospitals.

– What about your challenges and the language barrier that you experienced?

– When I think of challenges I think of my first two or three weeks in my city. Not so much being in a new place but just what comes with being in a new location where everything takes just a little bit more effort, a little bit more mental effort, a little bit more emotional effort. Sarah mentioned that you have to kind of get over this image, you want to do everything right, you want to go to the grocery store with no awkward moments or mishaps but that happens. And I think that the main challenges for me, like you get to the point a couple days after you move to your city where after a lovely orientation and meeting your cohort you’re like ‘Oh wait, I’m alone right now and I don’t know the stuff when I need to go to the grocery store, I don’t yet know where the gym is, I don’t yet know where to get school supplies, I don’t yet know where to get X, Y or Z’. But the important part in that is the word ‘yet’; you will find it. I think for me it was helpful getting into a routine, very early on and once you get into your routine you’re going to be passing by people on the street that you know, that you see over and over. The place becomes a lot more familiar. And within those routines you’re going to be meeting new people, whether that’s at the university. And I think that leaning on our cohort was very helpful for me too. In my study, a lot of people do speak English and it was more so that I would be walking around the city and seeing signs and be reminded ‘Oh I’m very illiterate’. But I don’t think that the language barrier ever really hindered me from getting something that I needed or procuring a need. Binding also speaks to the people in my city, people that were helpful. One of the things I think I value most is going up to someone, at first the first sentence ‘Oh do you speak Polish’ you speak in Polish and then it’s like a confidence boost and you’re like ‘Oh wow I fooled them’. But you have to convince them that you actually don’t, that you need help or whatever.

– The thing is, I think even just trying. I’m in Lublin, there is a lot of university students there, most young people working at cafes speak English and they told me it’s easier because their English is better than my Polish, just order in English, they don’t want to deal with it. Which is fair, but even if you try; when Alex was talking I was reminded of this time I was waiting for a bus and this older woman who did not speak English, I was kind of trying to talk with her because the bus was late and she adopted me for the next hour when the bus was late and I kind of followed her around and it was a very pleasant experience. But you end up with these very strange things happening that you couldn’t explain besides just ‘Poland.’ but they are lovely things [I kind of like that] [Yeah].

– What would you say is the easiest and the hardest part of teaching?

– Well for me I think the answer to both of those might be students. I always say that the best part of being here is the people and the students are a part of that and they are amazing. I joke with them that their English is better than mine. Sometimes I make a mistake and they’re like ‘Excuse me, was that slang because I heard other native speakers do that’ and I’m like ‘No, we’re just wrong’. But it’s a very great environment, almost always, however there is an interesting dynamic because I think for the three of us, we are quite young members of the cohort. We just finished our Bachelor’s and went into teaching and it can be difficult being so close to age with your students. It’s hard being the fun American teacher and also having set boundaries. It’s very possible to walk the line and I think we managed to do it, but that’s just something to be mindful of. Also for me something that was difficult with teaching was when it came to grading, because I had to grade these generalized exams for students and there were other people in the faculty grading and I was the only one that was a guest and I thought ‘Okay, this is so these students can pass, what if I’m not grading it the same as a Polish instructor is, and I had some concerns about that. But at the end of the day it was all fine, you always ask for help and they are like ‘Oh no, no, it’s fine’, so the things I had a difficult time with ended up just working out. But definitely with the students, finding the line between professionalism and fun American guest instructors is an important thing for sure.

– I definitely agree with that. I think, you know, our students, I think in Poland, at least in my region, there are not a lot of young teachers in the area so seeing me is like a breath of fresh air. And also I’m American, we’re American, so that was also a breath of fresh air. The students feel they can connect with us more. But also since we’re similar in age, we do similar things, it’s like ok, but I’m the teacher and you’re a student. Another thing is connecting with the students. I think some of my students, most of them, were into it, very involved but there were some students I literally had to pull teeth to get them to speak. I feel like they were just really self-conscious about talking to a native speaker. They didn’t want to say the wrong thing, they were like ‘do I speak in this type of tense or this type of tense?’. I’m like ‘no’.

– The easiest part for me was relationships with students. I like how Sarah was talking about, navigating the line between you are in a position of authority in your class and you want to make sure you are stewarding that well, making sure the students are learning what they are supposed to be learning, practicing what they are supposed to be practicing. But at the same time just because we are so close in age to them, I think there is this natural interest or appeal. We are from another country, we are their age and I think the students really did appreciate having us in their classroom. I think if you are genuinely trying to create a supportive and comfortable atmosphere in your classroom, the students will naturally gravitate towards you. And again, you already have this kind of interest, you are a foreigner and a native speaker. A lot of students haven’t really encountered that in their educational experience. So I think relationships with students in the classroom was one of my favorite parts. A lot of classes involved discussing with groups or discussing with students or in pairs so you are naturally going to form these relationships. The hardest part for me I think is grading, mainly because you are passing to a degree your judgment on an individual. And you are like ‘wait, but I really want you to know that you are communicative in English and outside of this classroom you will be just fine, you were able to talk with me and I understand you just clearly’. But just from the administrative side of things, navigating grading and being able to grade and check off these administrative tasks.

– I think another thing was some of my groups were all at different levels in English. I had some students who didn’t speak English at all so they knew nothing that was going on in my classroom. So I’m like ‘what I am supposed to do, can I give them maybe to a different class where the level is more appropriate for them, and if that’s not possible, what can I do’. And that was really hard to navigate. I had a lot of students who were translating to each other but that was really hard.

– What did you do? Did you divide the class in a way?

– We did a lot of group work and I purposely paired them up with students that aren’t translators with them. Or maybe 2 students who aren’t that good at English together and I paired them up together. Or I would have activities where they have to present something, like 10 minutes, do your research and then have to present. So I got them to do that and I got their English to come out or I would tell them ‘we have this presentation, every week we are going to work on this, and you are going to get more practice in’. So lots of that.

– Seeing the progress as you teach the class – is it a really rewarding thing?

– Yeah. I have seen…So my students are in the linguistics department or English. They are very good at language so in the university it’s not so much progress as it is just the use and finding idioms and talking about these things. But with my conversation group that I meet with outside of my university duties, seeing their progress is really cool. Even just the pronunciation or they will learn a word, write it down and will use it the next week. So that’s cool. It’s really great.

– It’s confidence. They were all so shy and scared of me the first days of school but now they’re like ‘hey!’ and confident.

– Expectations vs. reality. What were the major differences, if you remember? Probably you do. Any disappointments? Any positive surprises?

– So one thing… My biggest concern was being a black woman in Poland. I was like ‘are people going to stare at me like I’m some fly on this wall? Is it going to be scary for me? Where am I going to get my hair done? I don’t know how to do my own hair’. So I did a lot of research back home, ‘ok, where are the nearest hair salons?’. I talked to a lot of former Fulbrighters that were people of color. And I’m like ‘how was your experience?’. When I got here, I got my hair salon, where I’ve been getting my hair done, and it’s been nice. And this idea of being stared at all the time – that didn’t really happen as much as I expected to be. And I mean there were some situations that were seriously uncomfortable but it wasn’t as much as I expected. So that was really great, and I had a really great experience.

– I can talk about my expectations and what I experienced as reality. I think coming into this grant I had envisioned developing a lot more relationships with people my age outside of the university in my city and that didn’t happen to the degree that I had envisioned it happening. Instead, I think I was able to cultivate relationships with a handful of other wonderful people in my city, whether that was other Fulbright people in my city or my Fulbright buddy, or different community members inside of my city. I think coming in we had this idea of what we wanted it to look like and then we see how it actually looks, and you’re like ‘wait, it’s the friendship and comradery that I actually desired’ and this is what I actually experienced.

– I’m going to be honest, I did not even… I don’t know if I can say I didn’t have any expectations but I truly did not know what to expect. Like I said earlier, I have never been to Europe and like, I don’t even know what I thought. But teaching-wise, I think I was not really surprised with things there but, like, other life adjustments. The first time I did laundry, I was like ‘ok, I can do laundry’. And then I get there, I look at the washing machine in Polish and I’m like ‘oh’. You know, so it’s these silly things that didn’t seem hard, became hard. And I didn’t expect laundry to be the biggest hardship I had the first week I was there. Anyways, laundry is resolved now. But little things like that that you don’t think will be hard, will be incredibly hard. Like going to the grocery store will be a massive success. Just getting out and going. It’s things like that that I did not expect.

For me it’s not the matter of if I’m going back to Poland, it’s a matter of when. I think I said this to you earlier but like, I will be back, it’s a known fact. It’s just a matter of when. So I think that can sum up my experience right there.

– Apart from the duties that you had at your host institution, did you engage in any community-oriented or outreach activities? And if yes, what was that?

– Yes, I did. So for starters I was working with the EducationUSA doing a lot of school visits, mainly in my region but also throughout Poland, and that was really fun. Personally I was also involved in the gym and I got a trainer and that was, like, the best thing ever. I trained for a marathon as well, I ran my first marathon in Poland. And that has been really great. It’s been such a fun experience doing all of these things.

– Yeah, we did a lot of school visits. I worked a lot with the American Corner. I would do guest presentations and some classes, meeting with teachers. It’s actually really nice I was able to connect with the harpist from the Lublin Philharmonic. I’m a musician so being able to talk to her was really cool. She was my first Polish friend so it was really cool. I think the biggest kind of involvement involved English education for me with the American Corner.

– My primary form of community engagement was going to the primary school outside of the city. Coming into the grant I had also envisioned going to many primary schools or school visits, but after my second or third visit to this one primary school I realized the value, and being able to invest time in this one place and this one community. And that was my primary engagement activity and I’m very grateful for it.

-If you were to name two benefits of your grant, what would it be?

-The people and the people. The people – the cohort, my mentor, my colleagues. That’s the biggest thing. And I think the second benefit is self-reliance. I feel like I have learned my free will, like I can simply hop on a train and go to some other Polish city for the weekend. I mean, it does seem silly but like I said earlier, everything is harder at the beginning and so you’re really proud of doing this kind of thing. And, like, you realize what you are capable of. That’s for sure, a lot of things that I did not imagine. I’m a changed person. And that sounds cheesy but it’s true. And I like the person I am so it turned out ok for me.

– Definitely the people, as we have been talking about. The people, not only how supportive you all have been, but just like I genuinely enjoy spending time with you all. And then second, I know we have talked a lot about these really fun experiences that we’ve had but I think like the role of an ETA does provide you with experience to develop soft skills and presentational skills, and how to ask questions when you need help. So as fun as the experience outside of the classroom really is, the classroom experience is very valuable, whether you plan to go into teaching or you plan to go down a different career path. You are cultivating these softer skills that I know will translate very well when we go back home.

– Even, like, we mentioned it’s our Polish culture class. But I have learned so much from my students about Polish culture, Ukrainian culture. It’s really wonderful, I have learned so much this year about so many things relating to anything. I mean, even the museum that I visited in Poland. I know about gingerbread now. You learn a lot. But I think the biggest learning comes from the interactions with the students.

– If I ever had a question, I would ask my students first. They know the answer, they know everything.

– I think my biggest take away from this experience is in regards to the idea of intersectionality in that we are not just one-dimensional people. We all have such different dimensions of our life. So I experienced this when I was teaching in the first semester, having these conversations with my students, I realized this one student that walks into the class isn’t just a Ukrainian student, he is also a student who is a son, and he is really into music, really into basketball, he really like to do this, this and that. I think when you look at people they are not just this one-dimensional person or creature. They have so many different complex emotions and so many different interests. I think it makes me want to be more curious about the people around me because I found that just asking questions and getting to know the person you are sitting next to or the person who is in your class, that’s where the bridges start to be built because you get to uncover who the person really is. And in some cases it doesn’t just build bridges, it’s turning down walls, and you get to build that bridge and develop those connections. So I’m a really big proponent of intersectionality and thinking about that, and that’s the framework of my mind as I live this experience.

– Yeah, you know, you have these buzzwords about the Fulbright experience – global perspective, cross-cultural engagement, but, like, it’s real. Like there is a reason they are used. And I would echo what Alex said about intersectionality. I really do feel like I have a much more global perspective. Now that I have lived here, I came here and listened, learned. And that’s been really valuable. So that’s definitely a lesson. But the other lesson I think is I have realized truly how much I can count on myself. I did not realize how much I could before, but you know, when you’re.. When it’s January and the sun sets at 3 pm, it’s dark out and it’s just rough and you’re alone, you learn to count on yourself. That’s something I’m proud of, I’m proud of the other people in the cohort, because I think perhaps we all learned that, at least a little bit. But those are the 2 things. But it’s hard to identify sometimes because there is a lot.

– Definitely agree with that. I also think we are stronger than we think we are, I think we play down our strengths and what we are capable of, but we are capable of so much more than we realize. We put ourselves in these situations, I’m proud of me, I’m proud of each other. We did it.

– Ok, last question from me related to all of this that we have talked about. When you think or hear “Fulbright”, what comes to your mind? Any word, any expression?

– Collaboration. Working with my cohort, working with mentors that aren’t American, that are Polish. Working with my Polish students. So collaboration. Working together to reach a common goal.

– Embracing change. Making it work.

– I like the term or the phrase mutual understanding. I’m pretty sure Fulbright uses that in one of their official statements. But I like the phrase mutual understanding because if something is mutual, it means both parties are attempting to meet each other in the middle or attempting to get to know one another. And when you look at the mission of Fulbright, and, for our example, the United States and Poland – it’s our attempt to get to know Poland and the way that the Commission and this country has welcomed us, it’s this country’s attempt to learn more about the United States and where we come from, so I really like the term mutual understanding. And I think that it applies really well to the Fulbright Program.

– I think everyone should have some type of experience, if they are able, to live abroad, I think it’s a very important thing to do. Because the experience you are going to get, the skills you are going to learn – that can transfer into any career.

– It would be really interesting to think about where our country, the United States, 30-40 years from now. If this kind of experiences continue and happened for more people.

– It’s life-changing.

– I mentioned this at the beginning of our conversation but it’s this idea that we thought that we were coming to Poland to be representatives of our own community. But I feel even more empowered going back to my own community in the United States and be like a representative of Poland. That’s something that I didn’t necessarily expect to have that position and I definitely didn’t expect to be as excited about having that position as I am now.

– Yeah. That’s a big one. That’s a really good one.