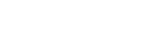

Prof. Daniel Aaron (1912 – 2016) was an American writer and academic affiliated with the Harvard University Department of English and American Literature and Language. Prof. Aaron was first American to visit Poland on a Fulbrght grant. He spent his Fulbright year (1962-63) as a lecturer at the University of Warsaw.

“Cultural representatives” by definition and consensus are expected to know something about the history and institutions of their respective countries and to be able to convey this information to foreign audiences without irritating or boring them.

William Fulbright believed that social and cultural interchanges of this kind enhanced “mutual understanding” between peoples, but he didn’t expect Fulbrighters to be salesmen or public relations experts. He wanted them to be seen and heard, to learn and to enlighten, and above all to “connect” with their hosts. Their success, in part, would be measured not just by what they communicated to foreign ears and eyes but also by how quickly and perceptively they examined their own preconceptions about the societies to which they were sent.

I saw Warsaw for the first time in the late summer of 1962.

Before then, Poland was largely a concoction of my imagination, a mix of rumour and sketchy facts. In this season of Cold War, Warsaw was said to be dangerous and crackling with genius.I had been warned about tapped telephones, bugged apartments, and beautiful ladies knocking at doors after midnight. Friends returning from brief visits to Warsaw and Cracow spoke with enthusiasm of the electric atmosphere, of sopping up vodka and gossip at the Bristol Hotel with high-flying artists and intellectuals. Polish films being shown in the States enhanced this image, one quite unlike the Poland incarnated for me in the large company of my fellow citizens in Northampton, Massachusetts, the descendants of Polish immigrants who had migrated to this area around the turn of the century. Galician Polish could be heard on Main Street and in the field and orchards east of the Connecticut River where – in the hope of improving my vision sufficiently to pass an American Navy eye test – I had suckered tobacco plants, weeded onions, cut asparagus, and harvested apples for Polish-American farmers.

But despite their presence, the Poland of my imagination was a blood-drenched land of fens and dark forests, of fields of sugar beets, of burning ghettos – a map dotted with unpronounceable names. After a few weeks in Warsaw, Iron Curtain fantasies lifted; words hardened into things to see and touch. On the first day, I had scouted for a corkscrew and learned my first Polish word, „korkociąg”. It took me a few months to pick up enough of the language to ask directions or make a request, to announce to a person jammed up against me on an overcrowded bus that I was getting off at the next stop – and to do so politely. In time I managed with the help of a grammar, a course of readings, and solicitous friends to puzzle out articles and stories, to travel on buses, trains, and planes with confidence, and to converse haltingly in a goulash of Polish, Russian, German, and French. By then I had given up the preposterous notion of becoming an interpreter of the New Poland and resign myself to making the most of my student contacts and of my sporadic encounters with a cross-section of the population outside the Academy. One bumped into the latter on planes and trains, in shops and restaurants, and at social gatherings attended by samples of the political establishment.

From the start of my venture, I had been a fearless generalizer about all things Polish, but I prudently confined my sweeping pronouncements to my journal.

There I could speculate without offence on the “Polish character,” spell out with Tocquevillian detachment why Communism could never take hold in Poland and they the system currently in operation was “organized inefficiency,” and ponder the political and social implications of the much-cited examples of “Polish humor.” I meditated on the term “Iron Curtain.” Wasn’t that a misleading phrase, geographically speaking? Weren’t there “curtains” – iron, bamboo, glass – hanging all over the world? I commented on the problem of winning the confidence of my Polish peers, as in the following journal entry:

„A social gathering of some sort in Warsaw and a friendly but guarded conversation with a new acquaintance. We were separated by a wall, not a terribly high one. He looks across it and smiles. You see, he seems to be saying, it’s better for us to be circumspect, not, mind you; because I fear reprisals – this is post-1956 Poland – but if we appear too friendly, too eager, well, that could be misinterpreted. So let’s greet each other on public occasions and then, perhaps, after we’ve had time to size each other up, we can meet more informally. I know you’re not the kind of American who writes articles about his Polish experiences as soon as he gets home. I know you won’t compromise your Polish friends who may have been indiscreet, but then we can never be sure, and there’s still much at stake for us here.”

Inhibitions of this kind gradually lessened in the comparatively relaxed interlude between 1960 and 1964. It wasn’t all that hard for foreigners like me to establish contacts with assorted Poles, although only a few years earlier a “mistake” might have cost a person his job or (almost as disastrous) his right to travel. This was apparent in the tense days of the “Missile Crisis” when people in the streets greeted me as an ally and taxi-drivers gave me thumbs-up salutes. Even so I couldn’t be sure that anything I said or did confirmed or corrected my students’ long-harbored views of the United States, or persuaded them to pay serious attention to America’s literature and history. Like their counterparts in other countries, their eyes and ears were tuned to American popular culture, to the contemporary American scene they hoped to see first hand, notwithstanding the resistance of their teachers to American as against English letters and culture, and the polemics of Party ideologists. For good or ill, the American virus was inescapable.

So what did it mean to be a “cultural representative” in Poland?

For this one, at least, it was an overwhelming introduction to a people and a country, its geography, history, literature, theater, music. It was also a corrective to unexamined prejudices and an illustration of the cliche that one’s first impressions are likely to be at once vivid and unreliable. Did my classes and talks and exchanges in Warsaw, Łódź, Lublin, Cracow, and Wrocław qualify or confirm the conceptions of my listeners about the United States? I shall never know – which is probably just as well.